It was individual rights, open markets, the rule of law, and break-apart empiricism that combined to enable the quality of life the developed world enjoys today.

At Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, the empirical component is provided by its Center for Dental Research (CDR) where “science,” as its director and associate dean for Research, Yiming Li, DDS, MSD, PhD, once remarked, “is the servant of ‘service.’”

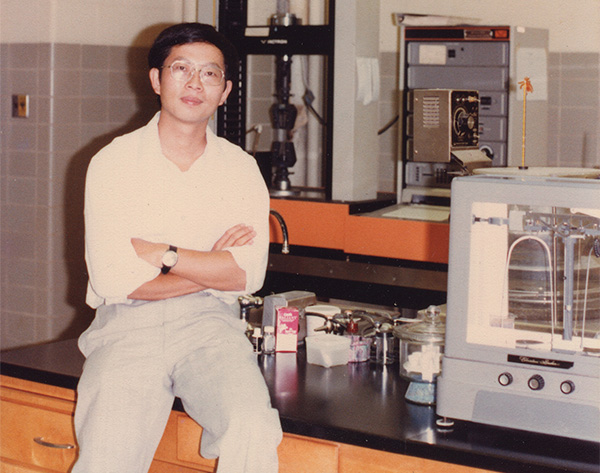

It is a congenial irony that the leader of empirical research at the School of Dentistry was born and raised in China and as a very young man was directed toward the life of a farmer. And it is unlikely that Dr. Li would be here today had it not been for a series of improbable and incongruous events.

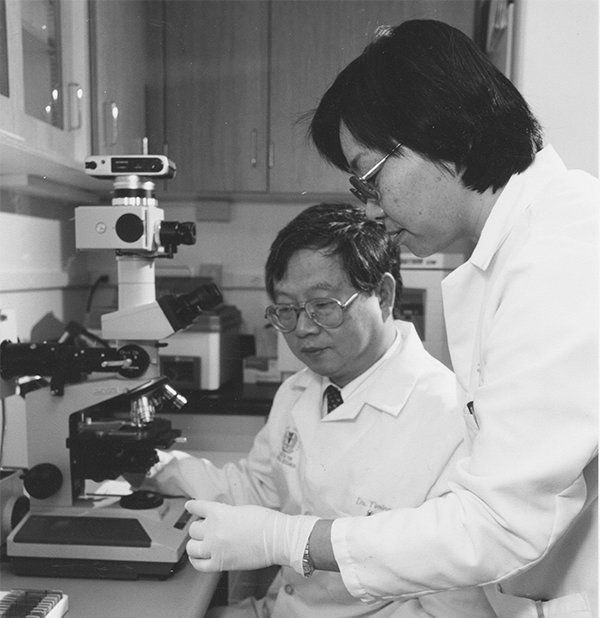

Drs. Wu Zhang and Yiming Li

One key episode that made possible the presence of Dr. Li and his illustrious wife, Wu Zhang, MD, professor, Dental Education Services and director, Research Services, and Sterilization Assurance Service, is that the administration of famously anti-communist President Richard Nixon initiated in 1971 and 1972 conversations with then communist Chinese leader Mao Zedong that eventuated in a thaw between the belligerents. The ensuing rapprochement enabled Dr. Li, a decade later, to pursue graduate studies at Indiana University, beginning in 1982, where he earned an MSD in dental materials and operative dentistry and a PhD in preventive dentistry and toxicology, and where Dr. Zhang researched the effects of in vitro and in situ demineralization on models of human enamel and dentin and studied the pharmacological effects of fluoride on medically compromised animals and patients.

Raised in revolution

Every accomplishment has a gestation period, some more painful than others. Yiming Li was born a couple of years after China’s revolutionary victors took over the country, the oldest son with four siblings that included an older sister, a younger brother, and two younger sisters. The mother of his oldest sister (a half sister, actually) died when the sister was born.

His father then married Yiming’s mother-to-be during the civil war between nationalists and communists. In 1949, four years after World War II, the communist faction prevailed and the People’s Republic of China was established. Yiming’s parents were living in Shanghai when the nationalists retreated. Most of the Chinese people had hoped for peace in 1945 when Japan surrendered, but the civil war erupted almost immediately, and that generation suffered profoundly.

Yiming’s father was born in a city about 200 kilometers from Shanghai and educated as a mechanical engineer. He found employment in Shanghai but never had stable work until the civil war concluded. Just before the end of the civil war, when the communist government took over Shanghai, his parents fled to the countryside where his mother’s adoptive parents lived on a small farm. His mother used to tell him that during the evacuation they lost everything, even their chopsticks.

Yiming’s mother’s childhood during the time before and during WWII and the revolution that followed was even worse than his father’s. She was 34 when Yiming was born. Because of their impoverished circumstance, the parents of Yiming’s mother had to give up three of their four children for some sort of adoption. Consequently, Yiming’s maternal grandfather and grandmother kept only one son. “Fortunately for my mother,” he says, “her adoptive father—my maternal grandfather—was a great man.” Originally, they accepted his mother with the intent of marrying her to one of their sons, a practice that once was very common in China. A young girl would be adopted and raised by a family with the intention of marrying her to an adoptive brother. Yiming says his mother “was always very appreciative of her adoptive father because he did not treat her according to custom. He allowed her to marry my father who was from the city and not related to the family at all.” Meanwhile, his adopted maternal grandparents had five children. “So, I had four uncles and one aunt from my mother’s adoptive family.”

“Before the family fled Shanghai,” Yiming learned later, “my father was a mechanical engineer and my mother was a textile factory worker. Her adoptive grandparents accepted the refugee couple on their modest farm.” All of Yiming’s mother’s adoptive (step) sisters and brothers were welcoming and helpful, he says. And his mother’s adoptive father was not only a farmer but also a chef. “My mother acquired those cooking skills, some of which she passed to me,” he says with amusement. This enabled Yiming to impress Wu, his wife to be, early in their acquaintance; “I cooked everything for her on her first visit to my home,” he recalls. So Yiming was his mother’s first child, born on her adoptive parents’ farm when they were in their poorest condition.

Yiming’s father had multiple gifts. “He walked around in villages sharpening knives and scissors for people to support the family,” Dr. Li recalls. “He did all sorts of work, anything he could find; meanwhile, most people were destitute. I really admire my father. He tried to do a lot of things. My father was a really, really great man,” he adds, his voice becoming husky.

A few years later, Yiming’a father designed and built a semi-automatic, sock knitting machine. “I saw that; I remember it,” he enthuses. “The operator would turn a handle and the machine would knit socks.” He imitates the staccato clatter of the machine. “My father was very capable, and, beyond that, he was certainly a great man. He never punished me; he always reasoned with me as far as I can remember.”

In the context of discussing his relatives’ religious beliefs, Dr. Li says, “As a matter of fact, my wife Wu’s maternal grandmother was a Christian. She and I really got along. I told Wu that her grandmother understood me the best.” He laughs. Wu Zhang, Yiming’s wife of 37 years, agrees that her grandmother, who lived until 1998 (92 years), was very, very nice,” adding that her family’s Christian beliefs began with her. “My grandmother and mother were very sincere Christians.” According to Dr. Zhang, her grandmother was widowed in her mid-twenties when the Japanese killed her husband, Dr. Zhang’s grandfather, during the Second World War.

Dr. Li’s earliest memory of his father’s real business concerned a tea house. “It is for certain that my father’s talents were not fully realized; and, in fact, in my opinion he was not a very good businessman,” he laughs, noting that his father let customers get away with IOUs or allowed them to run up tabs that they never paid. “After awhile, my father could not sustain the business and closed the teahouse. It was hard. My father and mother had to do everything. I wasn’t old enough to help.”

Dr. Li believes that his education was quite good. His father had financed grade school and high school education for his five children. When the universities were closed during the Cultural Revolution, Yiming’s dream of becoming an engineer or doctor appeared to be doomed. He worked on a vegetable farm. He learned gardening, the use of farm machinery, the raising of pigs, and the navigation of boats. He is convinced that this difficult experience taught him a lot about people and society as he worked the land, as well as a variety of skills that included electrical work, plumbing, and boat piloting. While working on the farm, reading provided Yiming a hobby. He would walk about three miles after work to the town library, but he convinced the local village chief to provide a nearby room and funding for a small library that he operated until he left for university education.

Daughter of revolution

Wu’s youth in many ways paralleled Yiming’s. “During WWII, because of the chaos, disease, and Japanese bombing of Shanghai,” she explains, “both my parents’ families not only lost everything, but also lost loved ones. It took decades to recover from this devastation.”

Growing up in Shanghai, Dr. Zhang says, “was easy, and our family had access to every convenience.” From second grade, she recalls, reading was her favorite hobby, adding that there was no TV or iPhone to compete with books. “I would try to find all the books I could to read; that was very attractive to me.” These included some novels written in the West and some, she says, translated into Chinese from other foreign languages. The schools she attended had libraries, and there were bookstores from which she could rent or purchase books.

But during China’s Cultural Revolution, all the schools were closed. Wu was taken at the age of seventeen with other students to a farm on Chongming Island, between the sea and the mouth of the Yantze River. She recalls being assigned to that farm. “There were no buildings for us, so the farmers made buildings out of bamboo for all the students. We lived in that difficult situation for about two years, then moved to a better brick house.”

.jpg)

“It was very harsh physically,” she recalls, living in unheated housing created with bamboo and hay, and planting rice barefoot in early spring. “This was the first time I realized,” she says, “how harsh life can be. After going through many difficulties, I learned how to face the challenges in my life. And looking back, it’s very rewarding. I am no longer fragile; I am a survivor,” she laughs. “There were no classes,” she recalls. “During the day we learned how to grow crops on the farm—boys and girls learning how to adapt and work as farmers. In the evenings most of my friends and I kept learning from text books.” It was repetitive labor that Dr. Zhang says left her much opportunity to think. “There was some fun,” she insists, “during stormy weather when we could stay in and read.”

In the fifth year of her farm experience, a position opened at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and noting her interest in science, the Academy selected her for the position. “I was very lucky,” she acknowledges. “In our generation we had a lot of talented students who had no such opportunity.” She subsequently also had the opportunity to pursue the study of medicine.

After the universities reopened, Yiming passed admission examinations and was accepted to take dentistry. His education at the College of Stomatology, Shanghai Second Medical University, now Jiaotong University, Shanghai, was tuition-free, but students were housed eight to a room stacked with double decker beds.

Collaboration

Yiming completed dentistry in 1977, in a class of 104 graduates, and was one of four selected from his class to remain as a member of the faculty. Although the school’s administration had slated Dr. Li for a position among them, after considerable pestering they permitted him to continue his education as a prosthodontics resident at Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, but he was urged to focus on dental materials research. He remained there for five years, teaching, practicing dentistry, and conducting research.

The doctors Li and Zhang met in Shanghai in 1978, not long after she graduated with medical credentials in the field of public health from Norman Bethune College of Medicine, now part of Jilin University, China, and while she was working as a researcher in the Chinese Academy of Science. “Our relatives introduced us,” Dr. Zhang recalls. When asked if she was looking for a high earning professional husband, she laughed. “Actually, in China at that time everybody in the same generation earned basically the same pay.”

Newlyweds

The two doctors dated for three years in Shanghai and married on May 1, 1981. At the time, Dr. Zhang recalls, the acquisition of assigned housing was difficult but relatively easier for married women. By the time they wed, she says, Dr. Li had just passed a series of intensely rigorous tests—university, city, and national—administered over a three-month period in 1981 that earned him a scholarship for the opportunity to engage in additional study outside the country.

Indiana University graduate student

Nineteen days after the couple was married, Dr. Li left for another city in China to do eight months of preparatory study in English with teachers from UCLA. He returned to his new bride in January of 1982 and, with the recommendation of his mentor, the associate dean for Research, Lichong Qiu, DDS, a graduate of Northwestern University School of Dentistry in Chicago, left seven months later, for Indiana University and a master’s degree program in dental materials mentored by Dr. Ralph Phillips, MS, D.Sc., author of Skinner’s Science of Dental Materials, and Melvin Lund, DMD, chair of operative dentistry at Indiana University, a pioneering LLUSD faculty member. Dr. Li treasures a gift of an autographed textbook from Dr. Phillips in which his mentor wrote, “No graduate student of mine has ever matched your capability, enthusiasm, and motivation for this field. You have demonstrated an unusual talent for research, and your record speaks for itself.”

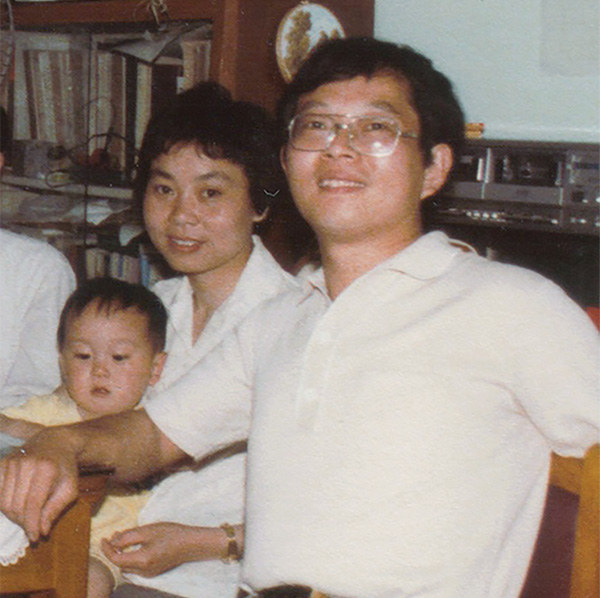

Jason Li with his parents in 1984

Dr. Li returned to China, MSD degree in hand, in the summer of 1984 to meet his 18-month-old son, Jason, for the first time and to spend a couple of months with his family before returning to Indiana to complete a doctorate in dental sciences awarded him in 1987. His PhD project, under the mentorship of George Stookey, PhD, generated nine articles, including seven published prior to his graduation, among which two were translated into Portugese and Spanish. He was offered a position and remained on the faculty of Indiana University. Both Dr. Phillips and Dr. Stookey served as associate deans for research and were designated distinguished professors at Indiana University School of Dentistry. “They are great mentors to me,” Dr. Li says, “they are also great gentlemen; I am very blessed to have been their student and colleague.”

Dr. Zhang and Dr. Li celebrate his doctorate from Indiana University.

During his 15 years at Indiana University, Dr. Li held appointments that included associate professor in the School of Dentistry and in the School of Medicine, director of the Cell Culture Research Laboratory, director of the Electron Microscopy/Confocal Microscope Facility, and director of the Biocompatibility Core Facility of the Indiana University Biomechanics and Biomaterials Research Center.

When the relaxation of China’s travel restrictions expanded, Dr. Zhang had the opportunity a year later to join her husband in Indiana. “I came to Indiana as a visiting scholar and worked in a research lab at the medical school. My previous experiences in research helped me to quickly adapt to new projects,” she explains. “For 12 years I had opportunities to conduct many dental research projects with colleagues at its medical school and dental school that resulted in more than 50 publications.”

In 1997, Dr. Zhang and Dr. Li became American citizens.

Recruited to LLUSD

At Indiana University, Charles Goodacre, DDS’71, MSD, who was earning his advanced degree there in prosthodontics (1971-1974), made the fortuitous friendship of the doctors Li and Zhang. “I don’t remember exactly when I became acquainted with Yiming, but I instantly recognized him and Wu as being in a class of their own,” says Charles Goodacre, DDS’71, MSD, distinguished professor of prosthodontics. “They are both individuals with exceptional personal and professional characteristics that embody true professionals.” After Dr. Goodacre became LLUSD dean beginning in 1994, he recruited Dr. Li in 1997 to be a professor and in 1999 associate director of the School of Dentistry’s newly named Center for Dental Research. Dr. Zhang was appointed research associate at the Center and assistant professor the following year.

Dean Charles Goodacre welcomed Dr. Zhang and Dr. Li to LLUSD.

In 2002 Dr. Li was promoted to become director of LLUSD’s Clinical Research Program. Two years later (2004), he was appointed director of the Center for Dental Research. In his leadership capacity, Dr. Li emphasized the essential question, “Is this material/device safe? Is it compatible with human tissue, blood, and/or saliva?”

His extensive scientific publications produced with colleagues that include his wife, and extensive lecturing in Asia, Australia, Canada, Europe, South America, and the United States achieved prominence that resulted in Dr. Li’s appointment as chair for the American National Standard/American Dental Association Specification for Biological Evaluation of Materials. This prestigious committee developed the first major revision of Specification No. 41—a 202-page report with Dr. Li as lead author that provides guidelines approved in 2005 for an American National Standard that determines biocompatibility for all dental materials, devices, and equipment.

Dr. Li was nominated in 2006 to serve a 3½-year term on the US Food and Drug Administration’s Dental Products Panel as its toxicology expert, addressing safety issues that took him to FDA hearings in Washington, DC, where he reveled in the democratic nature of his adopted country and the transparent nature of the applications for approval of dental materials, devices, or drugs. “Everything is transparent,” says Dr. Li, “and the panel members’ votes are independent. We don’t even discuss the issue with other panel members during breaks.”

In 2007 Dr. Li was appointed chair of the newly formed committee for the national standards for tooth bleaching materials and convener of an international standards committee on tooth bleaching materials. He also has collaborated with nine laboratories around the world to devise methods for analyzing fluoride in biological samples; and the CDR is studying, among other areas, tooth bleaching, gingival health, oral microbes, restorative materials, and oral odor. LLUSD CDR has been dominant in research regarding tooth bleaching and color measurement. Dr. Li has been quoted by big media in answer to the question, Can teeth (in this case the teeth of a beautiful model) be made too white? His reply: “It can. A general guideline is that the teeth should not be whiter than the whites of the individual’s eyes.”

In recent years, external research funding generated for the School has exceeded $2.0 million annually. “This would not be possible,” says Dr. Li, “without everyone’s diligent efforts and the support from the School. I am honored to have the opportunity to serve on this prestigious faculty.”

Accompanied by then Dean Ronald Dailey, PhD, and LLUH President Richard Hart, MD, DrPH, Dr. Li prepares to cut the ribbon.

Perhaps the most tangible testimony to his dedicated efforts is the 5,600 square foot, state of the art research facility in Chan Shun Pavilion that opened in February 2015 and now houses the Center for Dental Research. “Research is a key component of our calling, as it enhances the prospect of wholeness,” Dr. Li stated at the grand opening, adding “how fortunate” he was “to be part of the founding team that worked with Carlos Munõz, DDS, MSD, the first director of the Center,” and “to have a capable and willing team who for all these years always makes diligent efforts to ensure the highest quality and timely completion of projects.”

Associate dean for research

Effective February 3, 2014, the Loma Linda University Board of Trustees approved Dr. Li’s appointment as LLUSD associate dean for research, “a well-deserved appointment that reflects the elevated stature Dr. Li has achieved in Loma Linda University and the broader academic dental community,” said Dean Ronald Dailey, PhD.

Dr. Li has authored 141 articles and book chapters and 193 abstracts. In addition, he has presented 153 oral and poster presentations. He has earned grants of over $28.7 million since coming to the United States – of which approximately $21.6 million have come through the LLU School of Dentistry.

“Dr. Li has been an exemplary colleague, mentor, and friend to faculty and students in the School of Dentistry for the past 20 years,” says Dean Robert Handysides, DDS’93. “During his tenure at Loma Linda, he has helped numerous clinical faculty members become involved in research programs that have enabled them to achieve faculty rank promotions,” Dr. Handysides adds. “In addition, he has helped to build the student and resident research programs to a level that has enabled LLUSD students to garner a disproportionate number of state and national awards, especially at the annual competition for student research table clinical presentations at the California Dental Association Convention.”

All of this explains why Dr. Li was honored in 2014 with the Loma Linda University Distinguished Investigator Award, in 2017 with LLUSD’s School Distinguished Service Award, and was designated during the School of Dentistry’s 2018 commencement as distinguished professor of Restorative Dentistry.

Dr. Li and Dr. Zhang perform research in the School of Dentistry's early lab.

Partners in science and service

When the couple first arrived in Loma Linda in 1997, Dr. Zhang says, “Yiming needed an office; I needed a laboratory.” Her first research space was a laboratory the retiring LLU microbiology professor, Leonard Bullas, PhD, had recently vacated. She worked there for a year until the University committed space for dental research in the old Loma Linda Motel where she continued her fluoride studies with faculty and students. She also began cooperating with nine other major international laboratories to establish Gold Standard methods for fluoride analysis.

It wasn’t long before Dr. Zhang recognized a need that became an opportunity. She started the School’s Sterilization Assurance Service (SAS) and Dental Unit Waterlines testing program. Dr. Zhang thought both the research and services could be managed together, thereby strengthening the overall research program. Her initiative was a significant factor in the growth of the School of Dentistry’s research activities, beyond the acquisition of essential intramural and extramural funding.

With the support of Dean Goodacre, in 1998 the school’s Sterilization Assurance Service was established and has grown to serve LLUSD alumni and many other dental professionals nationwide. Dr. Zhang expresses appreciation to Kathleen Moore, MHIS, director, Continuing Education, Alumni Association and Marketing, “the School’s office of marketing, and its alumni journal editors, who have been very helpful for many years in promoting it through the alumni journal and newsletters.”

At the end of 1996, an “ADA statement on dental unit waterlines” was published by the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs that documented the serious contamination of waterlines in dental practices (J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:185-189). “Not many people are aware,” Dr. Zhang says, “research has shown that in newly installed dental unit waterlines, microbial counts can reach 200,000 CFU/mL within five days. In fact, counts as high as 106 CFU/mL of dental unit water have been found in untreated dental unit waterlines.” Having read the available research, Dr. Zhang was convinced. “I felt this is important as a potential public health risk, and I wanted to research it not only for the patients who directly receive contaminated water, but also for our fellow dentists who spend decades inside dental offices exposed to the risks of infection while treating patients.”

There was another niche between microbiology and dental practice to which Dr. Zhang thought the School could make a significant contribution. She collaborated with the ADA research lab for ten years to issue the first edition of ISO standard 16954 Dentistry — Test methods for dental unit waterline biofilm treatment, which was published in July 2015.

“In 2000 we started LLUSD’s Dental Unit Waterline Testing Service,” Dr. Zhang recalls. Subsequently, the service has provided waterline testing for dental offices in 43 states that include those of universities, large dental organizations, and many dental offices. At the same time, she collaborated with Joni Stephens, RDH, EdS, Professor Emeritus and former chair, Dental Hygiene, LLUSD, Dr. Munõz, and James Kettering, PhD, professor, microbiology, LLUMC, in the exploration of ways to evaluate and solve dental waterline contamination problems even as the CDR lab continues to monitor waterline quality for LLUSD. “I feel happy that LLUSD is able to provide clean water for patient treatment that is safe for everyone in all our clinics,” she says with a smile. “We also provide free consultation in the effort to help other dental offices solve dental waterline problems.”

In 2012 Loma Linda University recognized the contributions of Dr. Zhang with its Distinguished Research Award—well deserved given her contributions to so many studies involving students, visiting scholars, and faculty ranging from tooth whitening to oral odor, from antimicrobial activity to laser treatment of human teeth. She sums up the laboratory’s productivity: “In the past 21 years, the lab has conducted over 600 funded projects.”

“In the early years at Loma Linda, Yiming and I focused in different fields,” she says. But then, even though his work was more clinical and hers more laboratory centered, they began collaborating. And by the middle of 2018 the couple had co-authored 126 scientific publications in peer reviewed journals. At the time of this interview, Dr. Zhang had 186 publications to her credit—70 articles and 116 abstracts.

Dr. Yiming Li and Dr. Wu Zhang became American citizens in 1997, and what a powerful ar-gument their contributions to the common good have made not only for e pluribus unim but for the School of Dentistry’s motto, “Service is our calling.”