Jung-Wei Chen DDS, MS, PhD

Cleft lip and cleft palate are among the most common birth defects in the United States. Presurgical orthopedic treatment of the cleft lip and palate has become the treatment of choice for many craniofacial teams. The purpose of this article is to address the importance of the dentist’s role on the craniofacial team, the benefits of using a presurgical nasal alveolar molding appliance (PNAM) prior to surgical lip repair, and to describe the procedure for treating patients with the PNAM appliance. The PNAM appliance not only molds the affected intraoral and extraoral structures, but also provides nasal support while molding the collapsed nostrils. The PNAM appliance is the treatment of choice for unilateral and bilateral cleft lip and palate patients. For several reasons the use of this appliance enhances the chances of a favorable outcome and, thereby, improves the patient’s quality of life.

Introduction

Cleft lip/palate cases occur in one of every 700 to 1,000 newborns in the United States.1, 2 The causes of cleft lip and palate can be multifactorial: genetics, drugs, vitamin deficiency or excess, cigarette smoking. Environmental and other unknown factors may contribute. Superstitions in some cultures attribute the cause of cleft lip and palate to a jinx. For example, in the Chinese culture some believe doing hard physical labor during the mother’s pregnancy could cause cleft lip and palate. This malady has sometimes been connected, in the Mexican culture, to the use of scissors during pregnancy. Regardless of the cause, infants born with cleft lip and palate face multiple, life-long health problems that need to be resolved. This protracted treatment journey can be very difficult for patients, parents and health professionals.

In the United States, infants born with cleft lip and palate will be referred to a craniofacial team that consists of a pediatrician, plastic surgeon, feeding consultant, speech pathologist, ENT specialist, pediatric dentist, orthodontist, oral surgeon, prosthodontist, social worker, etc. Dentists play an important role in the treatment, providing presurgical soft/hard tissue molding, regular dental checkups due to high caries risk, orthodontic treatment, orthognathic surgery, and speech prostheses.

Dentist’s role in treating cleft lip and cleft palate patient

From birth into early teen years, regular dental checkups and an aggressive oral hygiene prevention plan are important for the cleft lip and palate patient. The initial appointment should be scheduled around the time of the first tooth eruption. Cleft lip/palate patients have a higher incidence of congenitally missing and supernumerary teeth, enamel hypoplasia, hypocalcification and ectopic eruption at the affected site. A cleft lip and palate patient may require follow-up dental visits at less than six-month intervals to receive sufficiently detailed instruction in oral hygiene (especially for ectopic erupted teeth), and fluoride application. In the early mixed dentition stage, orthodontic evaluation should be obtained in order to achieve optimal timing for initiating orthodontic treatment. The oral surgeon and orthodontist will determine the best timing for an alveolar bone graft and possible orthognathic surgery. Later, if the patient has speech problems or inadequate velum closure, a speech bulb or palatal lift appliance may be needed. If spaces due to congenitally missing incisors can’t be closed by orthodontic treatment, an implant or traditional fixed prosthesis may provide the best function and esthetic result.

Presurgical orthopedic or soft/hard tissue molding of the cleft lip and palate has become the treatment of choice for many craniofacial teams. This treatment modality is used to reduce the soft tissue cleft and facilitate lip repair. It precludes the need for lip adhesion with the attendant operative risks, expense, and potential tissue damage.

History of presurgical orthopedic soft/hard tissue molding

Presurgical orthopedics for the treatment of cleft lip and palate has been in use since the early 1500s, when Franco described the use of an extraoral head cap prior to surgical intervention. In the late 1700s, numerous researchers and surgeons began to experiment with bandages over the prolabium to stimulate muscle retraction with force, compressing the premaxillary region. In 1844 Hullihen used adhesive straps to prepare and close alveolar clefts prior to surgery.7 In 1950, McNeil developed an oral prosthesis, similar to an obturator, to approximate the cleft alveolar segments. He modified his appliance so that he was able to reduce the cleft by reorienting the direction of facial growth.8 Many orthopedic presurgical techniques have evolved.7, 8 Huebener and Liu3 classified the appliances as intraoral, extraoral, surgical, postsurgical, active or passive.

In the early 1980s Latham developed the pin-retained orthopedic appliance to exert a forward force on the posterior segment of unilaterally cleft maxillae. For bilateral clefts he designed a slightly modified appliance to control the posterior width of the maxilla, while retracting the premaxilla with a light constant force by means of a staple and power chain.9

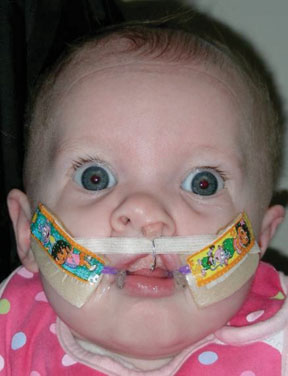

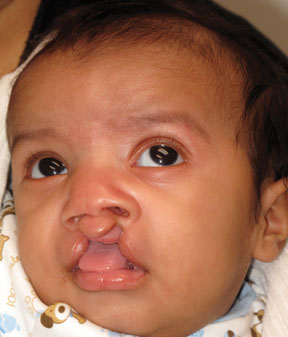

Twenty years ago, Grayson and Cutting introduced the presurgical nasal alveolar molding (PNAM) appliance. This allows surgeons to repair the lip, nose, and gingiva with one surgical procedure. This appliance not only molds the affected intraoral and extraoral structures, but also provides nasal support to mold collapsed nostrils. It improves the position and symmetry of nasal deformities (Figures 1, 2, 3), and has shown significant reduction in the size of the cleft intraorally.

The PNAM appliance was developed as an improvement over the Latham appliance.7, 10 This newer appliance takes advantage of the plasticity—and lack of elasticity—of the neonatal cartilage during an infant’s first two or three months.7, 11, 12

Objectives of Presurgical Nasal Alveolar Molding (PNAM) appliance

The objectives of PNAM therapy for unilateral and bilateral cleft patients are, 1) approximate and align the alveolar segments, 2) correct the alar base and cartilage of the affected nostril, 3) reposition the philtrum, nasal septum, and columella along the midsagittal plane, and, 4) lessen closure tension after lip repair.7, 8, 11, 13 It also improves certain functions, such as swallowing and breathing, through the elevation of the collapsed nostril.

Clinical procedure of PNAM appliance

The PNAM is fabricated from an intraoral impression of the maxilla, which needs to be handled with caution. If the impression is taken in a clinical environment, a small-tip suction device and oxygen mask should be ready. The impression material should have enough tensile strength to prevent impression material breakage and potential swallowing by the infant. A constant neck support should be used during the impression. The base of the molding appliance, made from acrylic resin, is polished and fitted for insertion. Two stabilizing buttons, added to the base of the appliance with a wire core, allow the direction of the buttons to be adjusted. Extraoral tape and denture adhesive paste can be used to increase retention of the appliance. This molding appliance is frequently adjusted by selectively grinding the area into which the alveolar bone segments are supposed to move. These gradual changes result in a more symmetrical maxillary arch.6, 7, 11, 12, 14

The success of the molding appliance is improved by taping together the lip segments across the cleft. The tape produces a controlled movement of the alveolar segments, improves the deviated columella, and moves the affected nostril into a balanced, upright position. The PNAM appliance assists practitioners in meeting the goal of presurgical orthopedics, which is to normalize mid-facial anatomy by reducing some of the forces that frequently cause collapse of the maxillary arch.

Parents are instructed to remove the appliance daily in order to clean any food debris and/or secretions from the appliance. The appliance is coated with fresh denture adhesive and reinserted.

Once the alveolar segment is reduced, one or more nasal stents are added. Each stent consists of a .025 mm stainless steel wire with a coil attached using a retention loop in hard acrylic connected to the labial flange of the molding plate.The extraoral portion of the wire ends in a bulb made from a hard acrylic core covered outside with soft acrylic15 for contact with the affected nasal dome and alar cartilages (Figure 3). The nasal stents provide support and mold the affected nostrils into a more symmetrical shape. The nasal stent is designed to apply selective pressure gradually to either stretch or pull the affected tissues of the nose.

External PNAM appliances increase columellar width, decrease columellar deviation, and increase the height of the affected nostrils, resulting in a more symetrical appearance. Internally they achieve reduced alveolar clefts as well as aligning and approximating the alveolar segments (Figures 5, 6).3, 7, 10, 11, 13

The Advantages and Disadvantages of PNAM appliance

The PNAM appliance offers several unique advantages. One is producing increased symmetry of both the soft and hard tissues. This in turn decreases the number of primary labial and nasal surgeries, which minimizes the extent of scar tissue formation. The molding appliance also serves as an obturator that facilitates the creation of negative pressure during the swallowing process. This increases the amount of formula ingested and shortens the feeding time, resulting in greater feeding efficiency. In addition the tongue can be trained to occupy a better position during both the swallowing phase and resting position. The ability of the PNAM appliance to treat both unilateral (Case 1, Figures 5-15) and bilateral (Case 2, Figures 16-23 below) cleft lip and palate patients clearly demonstrates its advantages (page 35).

Case 2: Bilateral complete cleft lip/palate

The following figures from Case 2 illustrate the treatment of a bilateral cleft lip and palate patient. The patient arrived for treatment at two-and-half months old—a bilateral complete cleft lip and palate. The premaxilla is protruded and located in the higher position with both soft and hard tissue defects (Figures 16 and 17). Figure 18 shows the patient—after three months of PNAM appliance therapy— ready for surgery. His alveolar segments are touching and his arch form is quite smooth and symmetrical. Figure 19-22 illustrates the surgical procedure. Fig 23 exhibits the encouraging post-operation results.

The primary challenge of the PNAM is that it is a labor-intensive procedure. It requires a significant parental commitment, without which the pediatric dentist’s continuing adjustments cannot be productive. In addition, minor trauma to soft tissues can occur because of the continuous use of tape to reposition the affected segments of the lip.11 However, overall the advantages far outweigh any disadvantages, as can be seen in the case of Jacob Youkhannas which follows the references.

Conclusion

Dentists play an important role in treating cleft lip/palate patients. With appropriate dental support as discussed above, the probability of a satisfactory result is much improved. Excellent results have been achieved using the PNAM appliance by increasing both hard tissue and soft tissue symmetry, which decreases the extent of surgery required for repairing the lip and palate. With the proper multi-disciplinary approach to dental treatment, cleft-lip-and-palate patients can anticipate favorable esthetic and functional results, and consequently an improved quality of life. The dentist can be the angel who makes a difference and enhances the life of cleft-lip-and-palate patients.

References

- Derijcke A, Eerens A, Carels C. The birth prevalence of oral clefts: A review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;34:488-494.

- Vanderas AP. Birth prevalence of cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip and palate among races: A review. Cleft Palate J 1987;24:216-225.

- Huebener DV, Liu JR. Advances in management of the cleft lip and palate. Clin Plast Surg 1993;20:723.

- Rosenstein SW, Jacobson BN. Early maxillary orthopedics: A sequence of events. Cleft Palate J 1967;4:197.

- Rutric k RE, Black PW, Jurkiewics MJ. Bilateral cleft lip and palate: Presurgical treatment. Annals of Plastic Surgery 1984; 12(2) 105-117.

- Rutrick RE, Cohen SR, Black PW et al. Presurgical orthopedic management of the unilateral cleft lip and palate newborn patient. Operative Tech in Plastic and Reconstr Surg 1995; 2(3):159-163.

- Grayson BH, Santiago PE. Presurgical orthopedics for cleft lip and palate. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM, eds. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:237-244.

- Maull DJ, Grayson BH, Cutting CB et al. Long-term effects of nasoalveolar molding on three-dimensional nasal shape in unilateral clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1999;36:217-244.

- Millard DR Jr, Latham RA. Improved primary surgical and dental treatment of clefts. Plast Reconstr Surg 1900;86:856.

- Grayson BH, Cutting CB, Wood R. Preoperative columella lengthening in bilateral cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 993;92:1422-1423.

- Grayson BH, Santiago PE, Brecht LE et al. Presurgical nasoalveolar molding in infants with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J 1999;36:486-498

- Nakajima T, Yoshimura Y, Sakakibara A. Augmentation of the nostril splint for retaining the corrected contour of the cleft lip nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;85:182-186.

- Santiago PE, Grayson BH, Gianoutsos MP et al. Reduced need for alveolar bone grafting by pre-surgical orthopedics and primary gingivoperiosteoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1998;35:77-80.

- Wood R, Grayson BH, Cutting CB. Gingivoperiosteoplasty and midfacial growth. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1997; 34:17-20.

- Bardach J, Salyer KE. Cleft palate repair: anatomy, timing, goals, principles and techniques. In: Shprintzen RJ, Bardach J, eds. Cleft palate speech management: A multidisciplinary approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book Inc.1995;102-136.

Dr. Chen introduces the Youkhannas to the Presurgical Nasoalveolar Molding instrument—a timeline

July 28, 2009

After seven ultrasounds, selection of a childcare center, and a personal commitment to nursing her expected child, Melissa Youkhanna heard her newborn, Jacob, gasping for breath as he left the birth canal. He was whisked away for special care. Then she heard the doctor’s words, "Your baby has a cleft lip. Don’t worry. It’s fixable." The doctor wasn’t yet aware that Jacob also had a cleft palate.

"I was shocked," Melissa says; "I ran the whole gamut of emotions. I was wondering, Did we cause this? Will I be embarrassed by him? Then they brought Jacob to me. I looked at his face, and I loved him."

Melissa checked out of the hospital early in order to join Jacob, who had been transferred from the Victorville hospital to Loma Linda University Medical Center. Her reservations at the childcare center and her commitment to nurse her child were no longer viable. Jacob would spend two weeks in the hospital learning how to eat. Melissa and Jack, Jacob’s parents, settled into Ronald McDonald House at Loma Linda. Family members—mother, father, an aunt, nieces and nephews—spent a week at a nearby hotel to support Melissa and Jacob. It took two weeks to find a bottle suitable for feeding Jacob.

Melissa went online. She absorbed information, communicated with moms across the nation who had children with cleft palates, sent for brochures. And she learned that Dr. Jung-Wei Chen, program director of LLUSD’s pediatric department, uses a unique new technique for correcting cleft palates. Upshot: instead of what can customarily be more than 10 surgeries, the Presurgical Nasoalveolar Molding (PNAM) appliance makes corrections that will require only four or five future surgeries. It reduces the size of the cleft gap, aligns the alveolar ridge, and increases nasal symmetry before surgery, Dr. Chen explained. And it would require parent-surgeon-dentist partnership.

October 2009

At two-and-a-half months of age, Jacob returned with his mother to Loma Linda University School of Dentistry and met with Dr. Jung-Wei Chen and the entire PNAM team for the first procedure. Weekly trips ensued: 90 miles round trip. The cleft, which started out at 9 millimeters, was diminishing. And Jacob’s nose was lifted.

November 26, 2009

Not quite six months old, Jacob underwent his first surgery. Part way through the surgery, the Youkhannas got a message from the surgeon, "Will you sign an agreement that we correct both palate and lip? It looks promising for us to do both today."

"It was a big surprise," Melissa recalls, adding, "Of course we signed." Jacob emerged from surgery, the shape of his lip corrected, the gum line fused, the palate closed. Melissa speaks knowledgably of the procedure: "Forty percent of the patients need a palate revision after surgery, but for Jacob there is no opening of the palate." His nose, she notes, has a barely noticeable flat side.

March 2010

When he was eight months old, the Youkhannas traveled to Georgia to introduce Jacob to family members. With no surgeries scheduled for the next two or three years, Melissa rejoices. "During one of two or more future surgeries," she says, "he’ll have a nose revision. We might as well make it perfect. And then there will be ortho, of course." Melissa speaks as a proud mother: "He’s like a normal baby. He eats regular food. He drinks from a regular bottle. He looks beautiful."

Jacob’s arrival placed the Youkhannas on a new program. "It was rough," Melissa admits. But she speaks courageously: "There’s no way I would leave him in child care. He requires extra attention. He will need speech therapy. I’ve become such an advocate. I want to help other moms." She looks upon the PNAM team as Jacob’s best hope for the future. Jacob is in competent care.